Design Attributes

- Latitude and Longitude references Foulness Island, where P3708 was discovered

-

Date code references Girdwood’s dogfight above the Essex coastline

- Dial design based on a slip turn indicator

- Crown modelled on the joystick gun platform fire button

- Merlin engine smelt from Hurricane P3708

Case

- 41mm diameter, Matt Silver #220, 316L stainless steel billet, with eight machined flutes

- Match machined, Matt black PVD, 316L stainless steel DSL lugs

- Matt Silver #220 exhibition back displaying a disc recast from the Merlin engine of Hurricane P3708

Main Crown

- Matt silver finished screw crown, modelled on the joystick gun platform fire button. 316L stainless steel with triple seal technology

Crystals

- Front: custom flat sapphire glass with blue AR coating on the internal surface

- Rear: flat sapphire glass with

reverse printed graphic

Movement

- Sellita SW200-1 ‘Top Premium Grade’

- 28,800vph

- 26 jewels

- Self-winding ball bearing rotor

- Power reserve ~41 hours

Dial

- Black enamel over brass substrate with multi printed indexes highlighted in SuperLuminova X1 luminous pigment

Hands

- White avionic style hands coated in SuperLuminova X1 luminous pigment. with matching Aeronautical white sweep hand

Dimensions

- 41mm diameter

- 13.5mm thick

- 22mm lug width

- 46mm lug to lug pin spacing

Strap

-

22/20mm Zero West custom military and aerospace gradecross-linked fluoroelastomerrubber. 1 fixed and 1 sliding keeper

-

Reverse sculptured relief

-

Matt finish

-

Steel buckle with etched black ZW logo

THE STORY BEHIND THE WATCH

With rumours of war abound, the twenty year old Alexander Girdwood was eager to join the Royal Air Force Volunteer Reserve. It was here he became an ‘Airman’ in name and began training to be a pilot at Prestwick in Scotland. Called into active service on 1stSeptember 1939, the same day that Nazi Germany invaded Poland and initiated WW2, Girdwood entered Flight Training School to polish his technique and fine tune his skills.

Posted to RAF Hendon on the 17thMay 1940, where the historic 257 Squadron was about to reform, he was one of the first arrivals alongside two other freshly trained Sergeant Pilots. 257 Squadron was battle ready with Hawker Hurricanes and fully operational by the 1stJuly and Sergeant Pilot Alexander ‘Jock’ Girdwood would enter the Battle of Britain confident of his ability and the valiant ‘Few’ beside him.

Hurricane P3708 was manufactured at Hawker Aircraft Ltd at Langley near Slough. This now legendary plane was an early Mk 1 Hurricane, designed by influential aeronautical engineer Sydney Camm. His clean single seat fighter, The Hurricane, was created after discussions with the Air Ministry regarding an increasingly urgent need for a mono-wing fighter plane. After trials, the initial design was quickly updated from fabric skinned wings to metal and armoured plating in front of the cockpit and an armoured windscreen.

It was designed for rapid engagement with enemy fighters and could outgun them with 8 remotely operated wing mounted 0.303 Browning machine guns. Powered by a Rolls-Royce Merlin engine, the Mk 1 had a top speed of 324 mph at 15 600ft. Camm’s design was simple but effective: the Hurricane could be manufactured quickly and was straight forward to maintain, its ease of handling and stable gun platform ensured it was adored by pilots and engineers alike.

After a successful test flight at Langley Airfield, P3708 was released to RAF No. 15 Maintenance Unit at Wrougton in Wiltshire on 22ndMay 1940. With the MU it was designated as a reserve aircraft before becoming closely acquainted with 257 Squadron and Sgt Pilot Alexander Girdwood at RAF Hendon as they entered The Battle of Britain.

Sunday 18thAugust 1940 has been described as the ‘Hardest Day’ in the Battle of Britain. The Luftwaffe flew an incredible 750 sorties, attacking airfields at Biggin Hill, West Malling, Croydon and Kenley. A critical radar station on the Isle of Wight was destroyed, and late in the afternoon another large scale attack fell on Kent.

Sergeant Pilot Alexander Girdwood’s first flight that day in P3708 was from RAF Debden at 05:20, a simple transfer before his squadron carried out three separate stints of convoy patrol allowing British vessels safe passage through the Dover Straits. After four hours of flight, a short and much needed rest was interrupted. An alarm sounded and tired pilots scrambled to their machines as 257 Squadron hurried to take on the Luftwaffe. Despite a multitude of reports from RAF Fighter Command and a 30 minute sortie, 257’s piece of sky was clear; no enemy fighter planes, no hum of heavy bombers, no contact. 1700 hours and the alarm sounded again; the last flight of the day. A scramble on tired legs into Hurricanes fuelled and ready. Angels 12 and contact over the Thames Estuary! 257 Squadron set upon a mixture of around fifty Heinkel and Dornier bombers escorted by Messerschmitt Bf 110s. Sgt Pilot Girdwood closed in quickly, bullets firing rapidly from multiple machine guns.

His Combat Report reads:

“I was Red 3. While following Red Leader at a height of about 12,000ft, we came upon a section of Heinkel 111s flying in a big bomber formation. Red 1 (Flt/Lt Beresford) made an astern attack on one of the HE111s. When he broke off firing, I closed in and fired until it started to smoke and go down. As I broke away bullets entered my cockpit which exploded and caught fire. After a struggle I managed to bail out and as I fell I succeeded in pulling the ripcord and untwisting the lines which wound round my legs. A toe of my right foot was fractured by a bolt, which was forced into it by a bullet. I received some burns and bruises. Subsequently I found that the HE111 had crashed near Foulness just beside my own plane. Two of the wounded German airmen were brought to the same hospital at Foulness as myself.”

Quick thinking and good fortune saw Sgt Pilot Girdwood limp away. Days later he was back in action soon to be fighting in some of the most intense days of the Battle of Britain under Squadron Leader Robert Stanford Tuck.

On 29th October 1940, 22 year old Sergeant Pilot Alexander “Jock” Girdwood gave the ultimate sacrifice and was killed in his plane whilst taking off during a raid on his North Weald airfield. He was one of Churchill’s brave “few” a young man fighting to maintain the sovereignty of Great Britain – Lest we forget.

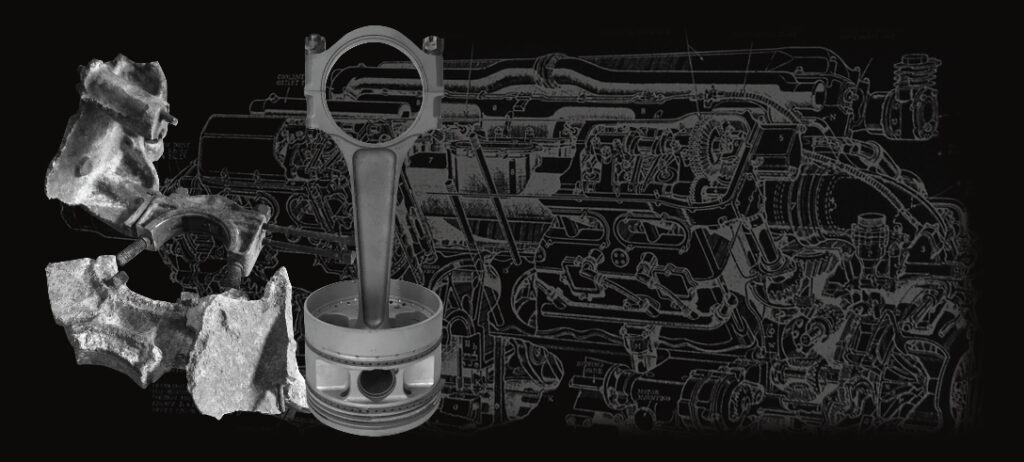

RECASTING HISTORY FOR THE H1-P3708

FROM DISCOVERY TO CREATION

DISCOVERY

After Jock got clear of his plane in those final moments, P3708 entered an ever steeper and faster dive, lasting just over 30 seconds before she plunged into the soft soil of Nazewick Farm on the north west corner of Foulness Island. The contents of her tanks erupted in an orange and yellow mushroom, quickly resolving into a pall of black smoke. But apart from leaving a blackened and smouldering crater there were few fragments to tell of the aircraft that had crashed there.

P3708 was deemed irrecoverable for salvage and was left to time and the elements. In the years that followed the farmer worked around the crater until wind-blown soil finally filled it in. P3708 remained undisturbed for 50 years until the East Anglian Aircraft Research Group identified the site and started to excavate in 1990. The remains of the wings which had been shorn off were found closer to the surface in burned and corroded condition. Further excavation revealed that most of the aircraft although badly crushed and damaged, was present at a depth of between 5 and 25 feet. Wood and fabric were just below the surface and as the site was gradually excavated its forgotten treasure was revealed. The tail fin, oxygen and compressed air bottles, steel tube fuselage frame, radio, throttle levers and instrument panel – assorted aircraft components which once made up the entirety of Hurricane P3708.

As a preservation of a moment in time, the firing button was still set to ‘fire’ and Girdwood’s gunsight had one of his gloves wrapped around it. Retrieved from the cockpit was Form 700 (signed by Flight Lieutenant Beresford), four bullet-holed maps of southern England and Girdwood’s oxygen mask. The remains of P3708 were cleaned, straightened and reassembled at the Norfolk and Suffolk Aviation Museum where it is now displayed. A reminder of our great British engineering heritage and the heroic pilots of the Battle of Britain.

PRODUCTION

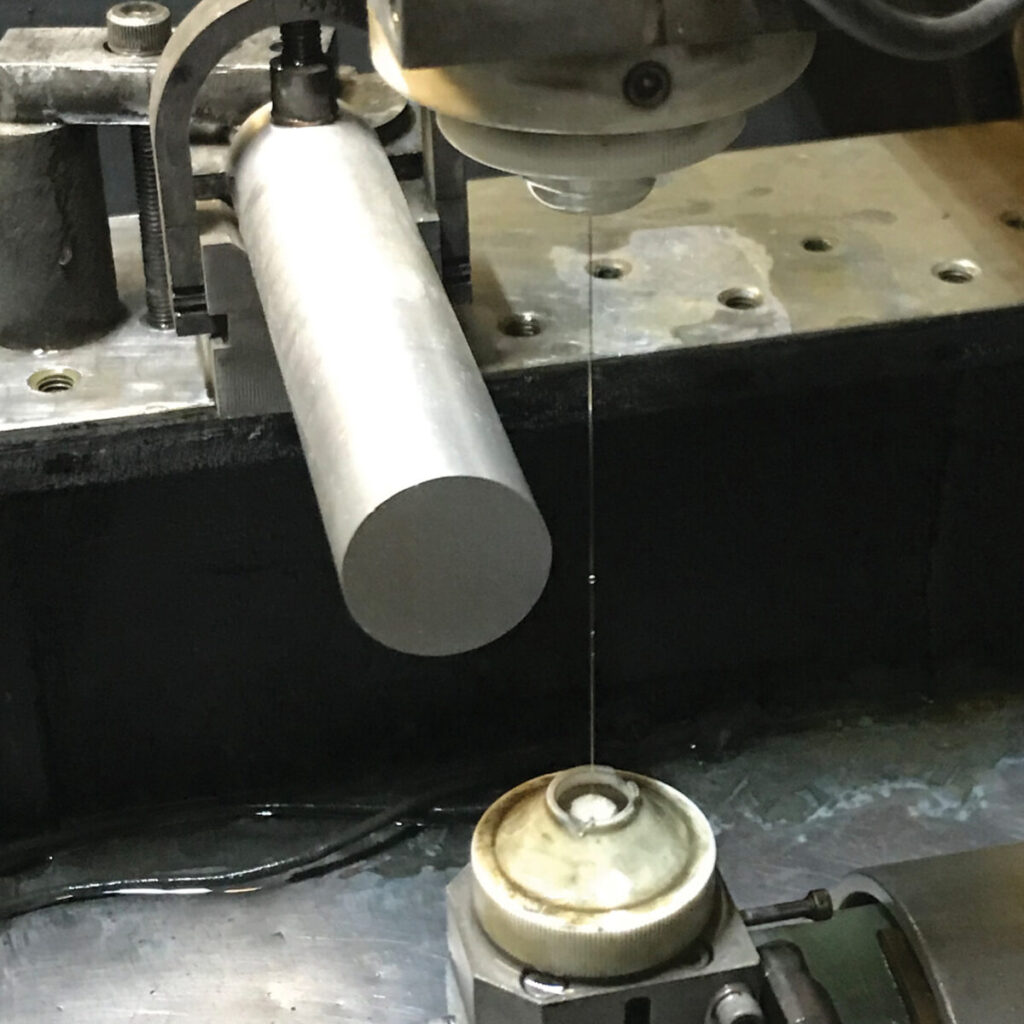

‘We made a firm decision to sand cast the alloy into round bars and then re-machine them to retain the integrity of Zero West, which is to billet machine our watch parts, rather than forge or cast them. During a local promotional photo shoot at Foundry Motorcycles, Chichester, we noticed that Tom, the owner, cast his own aluminium alloy parts, so we discussed the possibility of him smelting our bars, which he did.

The rough engine casting smelt material had corroded steel bolts, bearing shells and lubrication points which needed removing before it could be added to the crucible, so we got to work with the angle grinder and plenty of brute force to remove any non-aluminium inclusions. When we considered the last time this material had been cast was to make the Hurricane engine crankcase nearly 80 years ago, re-melting the aluminium was a moment that was both exhilarating and poignant. We were nervous about sand casting our precious RR-50 alloy but thanks to the skill of Tom, the size of the parts and their simple form, the results were impressive.

After pouring, the cast parts were carefully knocked out of their sand box moulds, quenched and cleaned, revealing new looking bars of precious Hurricane RR-50 alloy. The cast bars were turned down to finished diameter and then the precious discs wire-cut from the billet.

RECOVERED RECAST REINVENTED